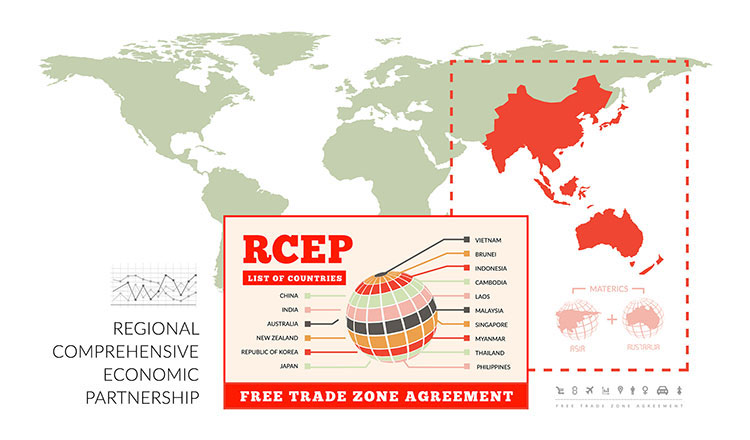

This is the fifth article covering the legal aspects of investment, part of a series of articles covering the economic, trade and investment impacts of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (RCEP) on Cambodia. The RCEP which has one of the most noteworthy investment chapters in any FTAs was concluded at a time of a historically disruptive year marked by a drastic decline of global FDI flows due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Hailed as a much needed shot in the arm for investment flows among RCEP countries, it is likely to shape global economics and politics in many years ahead, with the spotlight firmly on the Asia-Pacific region.

The RCEP creates an enabling investment environment with greater predictability for investors throughout the region by providing a strong platform to expand investment and trade in services with various provisions easing investment restrictions amongst RCEP countries. It contains new generational types of provisions regulating not only trade in goods and services, but also including various objectives pertaining to free market and fair competition. It is emblematic of the regional shift away from bilateral investment treaties (BITs) in favour of the development of FTAs where for the last three decades, BITs have seen its number dramatically dwindling.

Because of the developmental diversity of RCEP countries, ranging from developed, developing and LDCs, FDI-exporting and FDI-importing States, the Chapter reflects a good balance of diverse national interests and development imperatives. It contains flexibility in investment rules which encourage investment, without prejudicing the host States’ ability to regulate for legitimate public interest, especially in the post COVID recovery period. However, it does not include dedicated provisions on environment and labour found in most contemporary FTAs. Of great interest to Cambodia is that the RCEP’s objectives to help drive foreign investment into smaller ASEAN markets, such as Cambodia and Laos, where companies seeking to take advantage of their low-cost environments but for regulatory uncertainty have hesitated to invest there.

It provides market access and protections for investors from all fifteen countries with, for the first time, provisions covering the four pillars of investments – liberalization, protection, promotion and facilitation. The covered investments include the following forms of investments such as: shares and other forms of equity participation; debt instruments; rights under contracts, including turnkey, construction, management, production, or revenue-sharing contracts; intellectual property rights and goodwill; claims to money or to contract performance related to a business; concessions, licences, authorisations and permits, including those for the exploration and exploitation of natural resources; and movable and immovable property and other property rights.

It contains a national treatment provision which obliges a Party to afford treatment to investors and covered investments of any Party that is no less favourable than the treatment it affords its own investors and covered investments, in like circumstances, with respect to the establishment, acquisition, expansion, management, conduct, operation, and sale or other disposition of investments in its territory. Foreign investors and their covered investment are to be accorded fair and equitable treatment (FET) and full protection and security (FPS) in accordance with the customary international law minimum standard of treatment of aliens.

In terms of performance requirements, it prohibits a Party from imposing certain types of performance requirements on investors that go beyond the WTO Trade Related Investment Measures (TRIMS) Agreement. Any of the following requirements are prohibited, i.e. to export a given level or percentage of goods or to achieve a given level or percentage of domestic content. It prohibits requirements to appoint particular nationalities to the board of directors and senior management positions in the businesses of covered investments. A Party may however require that a majority of the board of directors be of a particular nationality, provided that the requirement does not materially impair the ability of the investor to exercise control over its investment.

There are obligations to allow all transfers relating to a covered investment to be made freely and without delay into and out of each Party’s territory. Such transfers include, among others: contributions to capital, including the initial contribution; profits, capital gains, dividends, interest, royalty payments, management fees, licence fees, and other current income accruing from the covered investment; proceeds from the sale or liquidation of all or any part of the covered investment; payments arising out of the settlement of a dispute; and earnings and other remuneration of personnel engaged from abroad in connection with the covered investment.

There is a denial of benefits clause where a Party may deny benefits to an investor of another Party or a third Party where their investments are in breach of the host State’s laws against money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism. There is an obligation not to expropriate or nationalise a covered investment unless it is undertaken: for a public purpose; in a non-discriminatory manner; upon payment of prompt, adequate, and effective compensation; and in accordance with due process of law.

Lastly, it provides for improved investment facilitation provisions which address investor aftercare, such as assistance in the resolution of complaints and grievances that may arise. These provisions are largely best endeavour and include typical commitments to simplify procedures for investment applications and approvals, promoting the dissemination of investment information and establishing and maintaining contact points.

Nationally, the timing of Cambodia’s new Law on Investment, promulgated last October 2021, reflects the evolution of the investment climate in the country. Its stated purpose was to establish an open, transparent, predictable, and favorable legal framework to attract more investors and enhance the quality and efficiency of investments in the country. It was intended to serve as a stepping-stone for Cambodia to becoming a more attractive investment destination by giving a wider range of incentives, guarantees, and protections for both domestic and foreign investors at the time of the entry into force of the RCEP. Between the RCEP and the new Law on Investment, Cambodia is prime to welcome a new wave of investors to its shore.