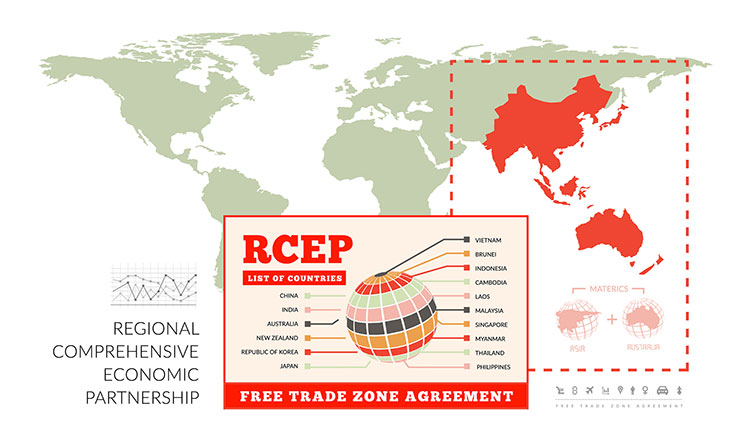

This is the fourth article on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (RCEP), part of a series of articles covering its economic, trade and investment impacts on Cambodia.

This article covers the legal aspects of the Trade in Services. Chapter 8 of the RCEP Agreement covers many aspects of modern economic life for many service providers. It provides a platform to expand greater trade in services through substantial removal of restrictive and discriminatory measures, either quantitative or qualitative, affecting trade in services.

At the RCEP level, at least 65% of the services sectors will be fully open to investors, with commitments to raise the ceiling for foreign shareholding limits in various industries, such as professional services, telecommunications, financial services, and distribution and logistics services.

These improved commitments are very important for many exporters as they look to undertake services-related activities to support their international business, such as establishing an in-market presence, forming commercial partnerships or providing after-sales services.

It builds on existing WTO commitments and delivers improved market access for services exporters in RCEP markets, going beyond equivalent rules in the existing ASEAN Plus One FTAs, with provisions on the reasonability, objectivity, and impartiality of domestic regulations affecting trade in services.

Cambodian services exporters to the RCEP region already enjoy market access benefits secured through various ASEAN free trade agreements and most recently with the Cambodia-China FTA and the Cambodia–ROK FTA.

In RCEP, these benefits have been consolidated and improved upon in a range of areas, allowing for greater transparency and usability for services providers hoping to identify new opportunities across the East Asia region.

The Chapter contains key elements for deeper services liberalisation in key services sectors like e-commerce, financial, and professional services. Modern and comprehensive provisions that establish high quality rules for the supply of services between Parties include obligations to provide access to foreign service suppliers (market access), to treat local and foreign suppliers equally (national treatment), to treat foreign suppliers at least as well as suppliers of any other non-RCEP country (most-favoured-nation or MFN), and local presence.

Similar to its negotiations made during the accession to the WTO, Cambodia’s commitments was driven by its updated development policies aimed, in particular, at attracting inbound foreign investment. Cambodia made commitments over 100 sectors and sub-sectors in the form of a positive list, much higher than it did during the WTO accession.

The commitments that Cambodia undertook shared the following characteristics. Generally, the limitation on Mode 1 (cross-border supply) is aimed at promoting investment in the country, including job creation and transfer of know-how.

For Mode 2 (consumption abroad), Cambodia generally had no restrictions, while for Mode 3 (commercial presence) the limitation is in line with GATS Art. XIX.2 and IV, since it aims at ensuring transfer of knowledge and technology and is the best way to improve the capacity of Cambodian professionals.

Several considerations motivated the trade in services commitments. First, Cambodia felt comfortable in taking on commitments in sectors where it had long had open policies regarding foreign participation and where they have served the country well, as in the case, for example, of banking and tourism services.

Cambodia also felt at ease in opening up sectors where its citizens could compete or cooperate with foreigners, for example in guide services.

However, where Cambodia saw an advantage in reserving part of a market for its SMEs, it did so. For example, similar to its commitment made under the WTO, it committed to opening its hotel market only for hotels of three stars or higher.

Second, Cambodia centered its negotiations on areas that would contribute most to improving those services required by businesses, thus enhancing the overall investment environment.

For example, Cambodia committed to allow foreign firms to operate in the areas of legal services (with some exceptions), accounting, auditing, management consulting, and transport.

Allowing foreign supply of retail services for supermarkets is also key to provide convenient services to the growing expatriate community. With the reopening of the economy in the post-pandemic period, services in support of an increased connectivity bear well for the hospitality industry, and certainly, for the food and beverages services industry.

Third, Cambodia made commitments in areas that will help Cambodians develop the skills needed for a modern and competitive economy, for example, it committed to allow foreign firms to provide higher education services.

As professional cooperation is also envisaged between RCEP countries to mutually recognize each other’s professional qualifications, upgrading skills will potentially be opening doors for market opportunities for dentists, engineers, and other professions. Cambodia undertook also commitments in the areas of health care and environmental services, which can contribute to the upgrade of its public health system.

From a trade in services perspective, the predictability of Cambodia’s regulatory commitments made to liberalise various services sectors will encourage more service suppliers in advanced economies, which have seen market saturation in their home country, to venture out into Cambodia.

This market opening will offer new joint venture or commercial collaboration possibilities for Cambodian services suppliers. As a matter of fact, 17 years after the country’s accession to the WTO, Cambodian companies have developed their respective strength and expertise in the market place.

Many have moved to manufacturing and improve its process ecosystem, with matured supply chain linkages. Others have moved their business online, resulting in a surge of digital shops and accelerating e-commerce growth.

The young and talented professionals, many of whom returning home one after the other from their overseas studies – thanks to the generosity of many development partners’ scholarships-, are quite well-placed to influence friendly business policies.

Their capabilities in mastering diverse foreign languages offered prospects as well for acting as a bridge with Chinese, Japanese or Australian employers.

Certainly, there will be many opportunities for these homegrown companies to develop innovative services to tap the regional supply chain chains, and most importantly, to emerge as credible business actors in the international business scene.