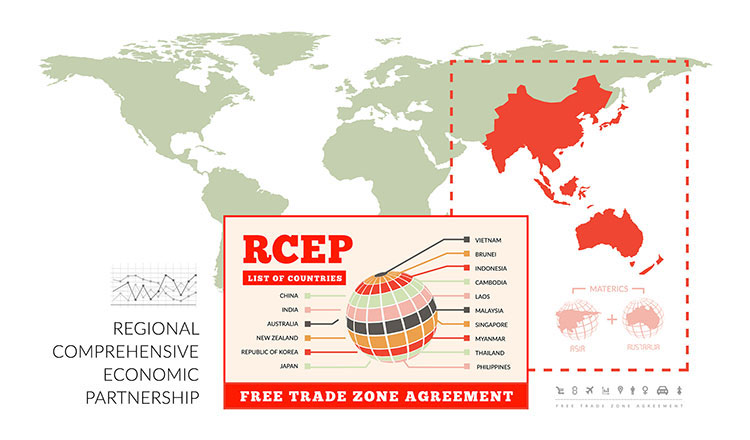

When Cambodia takes on its ASEAN chairmanship in January 2022, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (RCEP) will enter into force. By virtue of its size and the diversity of its membership, RCEP will become a solid building block for advancing further trade liberalisation in the Asia-Pacific. More importantly, it will mark a major step forward for the world, at a time when multilateralism is losing ground and global growth is slowing down. This article is part of a series of articles covering several aspects of RCEP and their economic, trade and investment impacts on Cambodia. After eight years of intense negotiations, a historic event was achieved by ASEAN with their development partners from China, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand with the signing of RCEP in November 2020. The formation of any FTA is a lengthy process, and RCEP is no exception. It has taken eight years, 46 negotiating meetings and 19 ministerial meetings to complete it. Even without India, there is no doubt that RCEP carries considerable symbolic heft. As the largest plurilateral FTA in the world, second only the WTO, RCEP joins the CPTPP, another important regional accord that went into effect in 2018. It covers more of humanity, with over 2.3 billion people or nearly a third of the world’s population as well as a third of the world’s GDP. The RCEP is a comprehensive agreement covering 20 chapters, including market access for trade of goods and service, investment liberalisation as well as a large number of trade related aspects, such as trade facilitation, e-commerce, intellectual property rights, competition policy, and government procurement. The most obvious element of RCEP is its ambitious reduction in tariff barriers. The total number of zero-tariff products in trade in goods exceeds 92 percent, while the opening up of at least 65% of services sectors, will certainly have the effect of stimulating more cross-border trade, investment and flows of people across the Asia-Pacific region. The second most sought after element is the harmonisation of different rules of origin of RCEP countries, and the setting up of generous regional-content requirements for a lot of products. In the case of travel goods manufacturers, once they can prove that their bags contain a 40% regional value content that come from any of the 15 RCEP members, they can export them to any of the 15 RCEP countries and enjoy preferential access. In fact, RCEP solves the ‘spaghetti bowl’ problem of ASEAN FTAs by unifying the set of trade rules for the Asia-Pacific region, which goes to the heart of the RCEP: the creation of a truly “Asian products” by way of managing the most controversial issue of the Rules of Origin (ROO). How does the RCEP benefit Cambodia? RCEP will provide Cambodian companies and consumers with increased commercial opportunities and partnerships. There will be more opportunities for local enterprises to boost exports, participate in new value chains in the region, and increase foreign investments. With this deep integration, global companies will find it more compelling to invest not just in China but also in the Mekong Subregion, which is recognised as a growth center as well as a very strategic regional hub. For the five ASEAN partners that are technically advanced nations, they have moved to high-end factories, where labour and production costs are relatively high. Their companies are keen to minimise costs by outsourcing finishing work to the less well-off ASEAN nations. For labour-intensive processes, the unified ROO will stimulate an increase of manufacturing investment interest in countries with lower-cost workers. Cambodian companies will benefit from enhanced flexibility in navigating between China, Japan and the ROK. It will also open up reverse opportunities for investment inflows, with Cambodia becoming one of the attractive destinations for international investors, due to its pivotal geographical location in the Mekong Subregion trade supply chains. Cambodian skilled construction workers and service workers, such as young IT programmers and software developers, could benefit from higher demand from countries like Japan and South Korea which are in need of these service workers. The growth of the business process outsourcing industry is also expected to grow. Another area of sustained focus in RCEP is e-commerce and digital trade, which looks promising for Cambodian SMEs. All these are potential opportunities in waiting. For Cambodia to enjoy the full benefits of RCEP, it takes time to prepare the ground for the private sector to get up to speed with this new trade paradigm. On the role of the Government, it is quite clear that it has made all the difficult works to conclude the negotiations. The remaining tasks are to go on a massive promotional campaign to explain and assist businesses to fully exploit all these potentials. On their own, it would be an uphill struggle for companies to understand all the specifics of the agreement and its schedules. Most of them are small and would not have the resources nor the expertise to grasp the intricacies of the trade rules. For development partners, the provision of ttechnical cooperation to address Cambodia’s productive capacity challenges is definitely a priority. Advanced industrialised countries like Japan, China, the ROK, Australia and New Zealand could assist Cambodian SMEs in developing better, more competitive products. New product innovations that increase the value-added contents of local products, which are still very modest, could boost its quality and attractiveness in the regional market. On the role of commercial banks, the local SMEs need to be supported to grow their market and business overseas. Without adequate trade financing the prospect of doing international trade will be dim, to say the least. Last, the signing of the RCEP signalled the Asia Pacific region’s collective commitment to stimulate the recovery of the global economy in the post-pandemic era. Business opportunities are up for grab for those countries who are ready, willing and capable. I truly believe that Cambodia is definitely one of them.

News